Ruby Blue's Red Flags: THE MYTH OF THE INDUSTRY PLANT: COMMODIFICATION & ERASURE

The TikTokification of the industry is a double-edged blade that is currently severing the jugular of artistic authenticity. During the isolation of COVID, we were sold a digital dream: the idea that anyone, anywhere, could go viral and bypass the gatekeepers. For a moment, it worked. It was a lifeline when the live circuit flatlined, allowing artists to find a tribe and even form bands across digital divides. But like every gold rush, the soil has been stripped bare. TikTok has devolved into a machine that turns everything, from literature to lyrics, into mere "content" and disposable commodities.

This brings us to the modern witch-hunt: the myth of the industry plant. The platform has blurred the lines between organic virality and paid-for saturation so thoroughly that the public can no longer tell the difference. We have conflated "nepo babies" with anyone who has a distant relative in the arts, and in this blurry mess, women are being disproportionately targeted as the primary suspects.

Take Lola Young. Because her great-aunt wrote The Gruffalo and she attended the Brit School, the TikTok jury has branded her a plant. It is a lazy narrative that ignores the material reality of the Brit School, a free institution where admission is predicated on raw talent, not the literary royalties of a relative [1]. Lola did not manifest out of a boardroom last week; she has been grinding since she was 14. If you look at the archives, you will see the sweat: open mic nights, support slots, and grassroots venues like Kansas Smitty’s or Bermondsey Social Club with 250-cap ceilings [2]. If she were the "plant" they claim, she would not have spent years in the trenches of the London circuit; she would have been parachuted directly into the O2.

Lola Young at Scala - Photo by Joe Baker

The label backing her now is not "planting" her; they are finally investing in a proven asset. As Dizzy often reminds me, a record label is an investment firm; they put money into PR to ensure their contract is profitable. That is not a conspiracy; it is the capitalist reality of the music business. Yet, when a woman’s hard work finally pays off, it is dismissed as corporate manufacture.

The vitriol spat at The Last Dinner Party and Wet Leg exposes a deeper, more systemic rot: blatant misogyny. The "industry plant" label has become a gendered slur used to undermine the agency of female creatives. You rarely see male-fronted indie bands subjected to the same forensic digital autopsies or multi-page op-eds questioning their "right" to exist [3]. When men have a polished aesthetic, it is called "visionary"; when women do it, it is "manufactured." This gatekeeping suggests that women are incapable of navigating the industry without a shadowy cabal of men pulling the strings. It is a refusal to acknowledge female competence and artistic ambition.

Ultimately, the obsession with origin stories distracts from the only thing that should matter: the music. If a song resonates with thousands of people, if it provides a sanctuary or a spark of rebellion, its "purity" on a spreadsheet is irrelevant. We are living in an era where the art itself is being buried under a mountain of discourse. We have forgotten how to listen because we are too busy investigating.

Furthermore, the "plant" narrative is a convenient distraction from the actual crises facing the working class in music. The real barrier for working-class musicians is not the existence of label-backed artists; it is the catastrophic decline of the UK’s cultural infrastructure. In 2023 alone, the UK lost 125 grassroots music venues, which represents 15% of the entire ecosystem [4]. This, combined with the decimation of arts funding and the astronomical cost of touring, is what truly penalises working-class talent. It is far easier for the public to dogpile a female artist on TikTok than it is to hold the government accountable for the structural divestment from our communities.

The most sinister element of this discourse is the erasure of history. Major labels often scrub a band’s grassroots past to create a "clean" narrative of overnight success. We saw this with The Blinders, a band The Zine UK championed from their infancy. Labels delete the digital trail of the people who supported them at the grassroots level to protect their "discovery" narrative. This is not the band’s fault; it is a corporate strategy that prioritises profit over the community that built them.

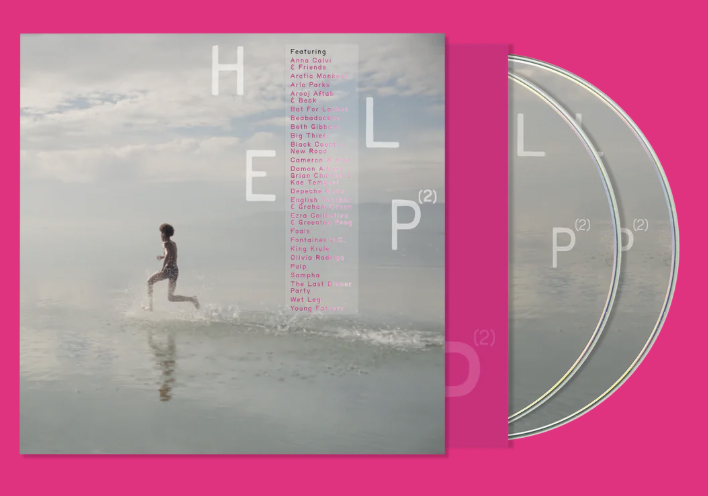

The consequence of this "plant" paranoia has reached a point of moral bankruptcy. We are seeing calls to boycott the Help2 charity album, a project raising funds for Warchild to support children in Palestine and other war zones. The justification? The presence of "industry plants" on the tracklist. It is a terrifying indictment of our current culture that people find the perceived "offence" of a label-backed artist more egregious than a literal genocide [5].

If TikTok had existed in the 70s or 80s, the "plant" label would have been slapped on David Bowie, Blondie, or Madonna. They had major label machines pushing them into the mainstream consciousness with massive PR budgets. To the outsider, they appeared overnight. To those in the know, they were the product of years of labour. Just because you did not see the work does not mean it did not happen. It is time to stop using "industry plant" as a weapon to gatekeep women and start looking at the labels and the systemic failures that are actually doing the erasing.

References

[1] Brit School Archives. (2024). Admissions Policy and Meritocratic Frameworks.

[2] Young, L. (2020-2023). Live Performance Archive: Grassroots Circuits and Support Slots.

[3] Hunt, E. (2023). Why is the 'industry plant' label only ever used for women? Refinery29.

[4] Music Venue Trust. (2024). Annual Report: The Crisis of Grassroots Infrastructure.

[5] Warchild UK. (2025). Help2: Music as a Tool for Humanitarian Aid in Conflict Zones.